2008, Folkestone / Coed Gwynant, UK

Tales of Space and Time

Converted Bedford Green Goddess, Douglas fir, books, and other media

Commissioned by the Creative Foundation for Tales of Time and Space,

Folkestone Triennial, 2008

The Morisons exhibited their self-sufficient wooden house-truck, customized from a decommissioned fire engine and containing, next to a stove and pot plants, a library of apocalypse-themed fiction. Tales of Space and Time, as it was called, embodied a jauntily over-optimistic attitude to surviving the end of the world, simultaneously mocking the ‘art will save us all’ attitude of some contemporary civic reformists. Art won’t save Folkestone. I hope something does though – something real, something solid.

Jonathan Griffin, Folkestone Triennial, Frieze, Issue 117 September 2008

__________

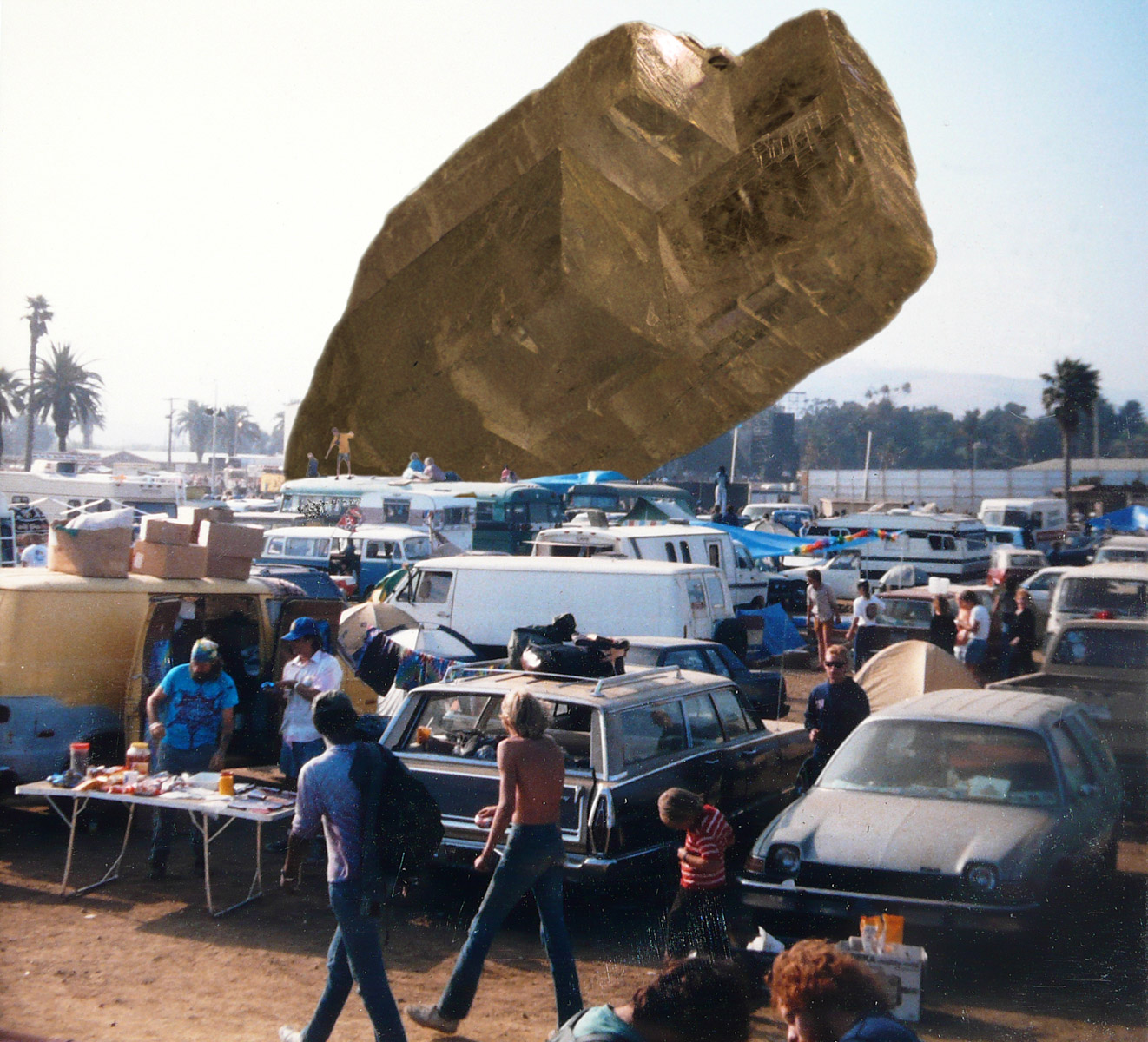

Made popular during the 1970s hippy movement on the west coast of America, house trucks are a symbol of freedom and a nomadic self-sufficient lifestyle. Following this tradition, the artists built Tales of Space and Time by hand using timber from Douglas firs grown in their own arboretum in Coed Gwynant, north Wales, and the body of a 1956 Green Goddess, an ex-army fire engine. Inside, the truck houses hundreds of volumes of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic science fiction, as well as bespoke furniture, including a stove, bed, and all the essentials in case of escape. Before they built the vehicle, they went on

a research trip to Oregon, where they tracked down some of the pioneer house truckers, and learned about the motivations for their choice of alternative lifestyle and their reasons for wanting to escape from conventional society.

The artists explain the choice of the vehicle: ‘We built it in the spring of 2008 in the true west coast house-truck spirit, felling and milling our own timber for the build. We chose a Green Goddess, a former military fire engine, to build our truck because it was a little more rugged and more in the modern survivalist vein than those of the New Age American travellers. We have a man who comes with a mobile sawmill to cut timber for us. When he arrived to work on this project, the Goddess was parked up in the wood. He told us that he used to be in the Royal Air Force and that these fire engines used to be stored, three high, in huge hangars on an airbase somewhere. There were so many of them that it was the job of a entire team of mechanics just to continuously service them. But these machines weren’t stored there to be used when firemen went on strike, but for when the apocalypse happened. They were kept in all readiness for that event. Our Goddess was built and put into service in 1956. The army decommissioned all their Goddesses last year. We don’t know if that is because they have replaced them or because they have decided that the end isn’t coming just yet.’

Commissioned by the Creative Foundation for the inaugural Folkestone Triennial, the truck was staffed during the summer months of the exhibition by a local science-fiction enthusiast and made regular daily stops around the town, lending books, holding talks, and welcoming visitors. Now permanently installed at Coed Gwynant, it has been remodelled and its collection of catastrophe books continuously added to, with a new expanded section of feminist science fiction.

Jonathan Griffin, Folkestone Triennial, Frieze, Issue 117 September 2008

__________

Made popular during the 1970s hippy movement on the west coast of America, house trucks are a symbol of freedom and a nomadic self-sufficient lifestyle. Following this tradition, the artists built Tales of Space and Time by hand using timber from Douglas firs grown in their own arboretum in Coed Gwynant, north Wales, and the body of a 1956 Green Goddess, an ex-army fire engine. Inside, the truck houses hundreds of volumes of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic science fiction, as well as bespoke furniture, including a stove, bed, and all the essentials in case of escape. Before they built the vehicle, they went on

a research trip to Oregon, where they tracked down some of the pioneer house truckers, and learned about the motivations for their choice of alternative lifestyle and their reasons for wanting to escape from conventional society.

The artists explain the choice of the vehicle: ‘We built it in the spring of 2008 in the true west coast house-truck spirit, felling and milling our own timber for the build. We chose a Green Goddess, a former military fire engine, to build our truck because it was a little more rugged and more in the modern survivalist vein than those of the New Age American travellers. We have a man who comes with a mobile sawmill to cut timber for us. When he arrived to work on this project, the Goddess was parked up in the wood. He told us that he used to be in the Royal Air Force and that these fire engines used to be stored, three high, in huge hangars on an airbase somewhere. There were so many of them that it was the job of a entire team of mechanics just to continuously service them. But these machines weren’t stored there to be used when firemen went on strike, but for when the apocalypse happened. They were kept in all readiness for that event. Our Goddess was built and put into service in 1956. The army decommissioned all their Goddesses last year. We don’t know if that is because they have replaced them or because they have decided that the end isn’t coming just yet.’

Commissioned by the Creative Foundation for the inaugural Folkestone Triennial, the truck was staffed during the summer months of the exhibition by a local science-fiction enthusiast and made regular daily stops around the town, lending books, holding talks, and welcoming visitors. Now permanently installed at Coed Gwynant, it has been remodelled and its collection of catastrophe books continuously added to, with a new expanded section of feminist science fiction.

Ivan Morison: What made you build your first truck?

Roger Beck: The first one I call my escape vehicle! I grew up in LA, a metropolitan, screwy city. And so it just got to the point where I just had to get out. So I left a whole bunch of stuff I didn’t want to get rid of at my parent’s house and got into my first house car and headed north. I couldn’t head south ’cause I had long hair and didn’t want to cross the Mexican border; I couldn’t go any further west; the east coast was nothing more than big cities to me and so I decided to go to Canada!

So, it was my escape route. I got to Oregon and then I did a stupid thing. Me and a friend ripped a tape deck out of a logging truck and I was arrested the same day and I was put on five-years probation. And in those five years I built my second house-truck that had a lot of problems. I drove it to California again to see my parents and my father and I built my third truck. He really helped me build a house on the back of a truck. I travelled most of my travels in that one.

I had the idiosyncrasy of trying to distinguish myself as a New Age American Gypsy and not a hippy living in a school bus with a bunch of mattresses in the back. That’s not a house-truck, that’s because you’re homeless and you can’t afford to live in an apartment, which you’d prefer to do. I had no desire to live in a house. I had my house; it was just on wheels.

Ivan: Was there anyone doing this before you in America?

Roger: For me, when you think about house trucks you’ve got to go back to the depression. People were living in rigs because they couldn’t afford to live anywhere else.

Ivan: Were you coming from a political standpoint at the time?

Roger: Well, a lot of the politics came out of the Vietnam War, trying to escape all of that, to be free. It was an era when gas was fairly cheap and the idea of being free was desirable.

Excerpt from a conversation with Roger D. Beck at his workshop in Eugene, Oregon, January 2007.

Roger Beck was one of the first pioneers of the house truck movement back in the 70’s on the west coast of America: A loose grouping of people who felt discontent with the ways in which they were being made to live, who struck out with a nomadic model for living of their own. We made a journey back in early 2007 to track down many of those early house truckers and to talk to them about what they were escaping from and to see if they had succeeded. We also had a notion that a new younger generation of Americans were now equally discontent with parallel political and social problems, and we wanted to see whether the idea of escape was still possible, or whether this newer generation were too embedded into to their culture to truly escape from it. Our findings to that are for another essay, but in summary the trip left us fascinated by the possibilities of the escape vehicle.

So to Folkestone, with its links to one of the greatest science fiction writers of all time, H.G. Wells, the inventor of one of the finest escape vehicles of all time, the Time Machine. What a remarkable vehicle that can take you to any point in the past or the future, where you can witness what became of mankind and the earth, and then be safely whisked away.

We wanted to build our own escape vehicle; one, a bit like the Time Machine, that equipped its occupant with the knowledge of every imaginable future and mankind’s solutions to these problems. We chose a Green Goddess, an old military fire engine, to build our house truck onto (little more rugged and more in the modern Survivalist vein than the New Age American Gypsies perhaps) and filled it with a library of the finest apocalyptic, post-apocalyptic and catastrophe science fiction literature.

For the duration of the Triennial the truck will tour around Folkestone; an incongruous addition to the usual street scene; open to visitors to borrow books and to read up on possible futures; a reminder to be prepared.

We built the house truck in the true west coast house truck spirit; felling and milling our own timber for the build. We have a man who comes with his mobile saw mill to mill timber for us. When he came to mill the timber for this project the Goddess was parked up in the wood. He told us that he used to be in the RAF and that these Green Goddesses used to be all stored, three high, in these huge hangers on an airbase somewhere. There were so many of them that it was the job of a whole team of mechanics just to continuously service these vehicles. The thing is that these fire engines weren’t all stored there for when the fire service went on strike, but for when the apocalypse did happen. These machines were designed and kept in all readiness for that event. Our Goddess was built and put into service in 1954. The army decommissioned all their Goddesses last year. I don’t know if that’s because they’ve replaced them, or whether they have decided the end isn’t coming just yet.

Ivan Morison, Folkestone Triennial, Tales of Time and Space, exh. cat., The Creative Foundation, 2008, p.80

Roger Beck: The first one I call my escape vehicle! I grew up in LA, a metropolitan, screwy city. And so it just got to the point where I just had to get out. So I left a whole bunch of stuff I didn’t want to get rid of at my parent’s house and got into my first house car and headed north. I couldn’t head south ’cause I had long hair and didn’t want to cross the Mexican border; I couldn’t go any further west; the east coast was nothing more than big cities to me and so I decided to go to Canada!

So, it was my escape route. I got to Oregon and then I did a stupid thing. Me and a friend ripped a tape deck out of a logging truck and I was arrested the same day and I was put on five-years probation. And in those five years I built my second house-truck that had a lot of problems. I drove it to California again to see my parents and my father and I built my third truck. He really helped me build a house on the back of a truck. I travelled most of my travels in that one.

I had the idiosyncrasy of trying to distinguish myself as a New Age American Gypsy and not a hippy living in a school bus with a bunch of mattresses in the back. That’s not a house-truck, that’s because you’re homeless and you can’t afford to live in an apartment, which you’d prefer to do. I had no desire to live in a house. I had my house; it was just on wheels.

Ivan: Was there anyone doing this before you in America?

Roger: For me, when you think about house trucks you’ve got to go back to the depression. People were living in rigs because they couldn’t afford to live anywhere else.

Ivan: Were you coming from a political standpoint at the time?

Roger: Well, a lot of the politics came out of the Vietnam War, trying to escape all of that, to be free. It was an era when gas was fairly cheap and the idea of being free was desirable.

Excerpt from a conversation with Roger D. Beck at his workshop in Eugene, Oregon, January 2007.

Roger Beck was one of the first pioneers of the house truck movement back in the 70’s on the west coast of America: A loose grouping of people who felt discontent with the ways in which they were being made to live, who struck out with a nomadic model for living of their own. We made a journey back in early 2007 to track down many of those early house truckers and to talk to them about what they were escaping from and to see if they had succeeded. We also had a notion that a new younger generation of Americans were now equally discontent with parallel political and social problems, and we wanted to see whether the idea of escape was still possible, or whether this newer generation were too embedded into to their culture to truly escape from it. Our findings to that are for another essay, but in summary the trip left us fascinated by the possibilities of the escape vehicle.

So to Folkestone, with its links to one of the greatest science fiction writers of all time, H.G. Wells, the inventor of one of the finest escape vehicles of all time, the Time Machine. What a remarkable vehicle that can take you to any point in the past or the future, where you can witness what became of mankind and the earth, and then be safely whisked away.

We wanted to build our own escape vehicle; one, a bit like the Time Machine, that equipped its occupant with the knowledge of every imaginable future and mankind’s solutions to these problems. We chose a Green Goddess, an old military fire engine, to build our house truck onto (little more rugged and more in the modern Survivalist vein than the New Age American Gypsies perhaps) and filled it with a library of the finest apocalyptic, post-apocalyptic and catastrophe science fiction literature.

For the duration of the Triennial the truck will tour around Folkestone; an incongruous addition to the usual street scene; open to visitors to borrow books and to read up on possible futures; a reminder to be prepared.

We built the house truck in the true west coast house truck spirit; felling and milling our own timber for the build. We have a man who comes with his mobile saw mill to mill timber for us. When he came to mill the timber for this project the Goddess was parked up in the wood. He told us that he used to be in the RAF and that these Green Goddesses used to be all stored, three high, in these huge hangers on an airbase somewhere. There were so many of them that it was the job of a whole team of mechanics just to continuously service these vehicles. The thing is that these fire engines weren’t all stored there for when the fire service went on strike, but for when the apocalypse did happen. These machines were designed and kept in all readiness for that event. Our Goddess was built and put into service in 1954. The army decommissioned all their Goddesses last year. I don’t know if that’s because they’ve replaced them, or whether they have decided the end isn’t coming just yet.

Ivan Morison, Folkestone Triennial, Tales of Time and Space, exh. cat., The Creative Foundation, 2008, p.80

Photographers’ credits

All’s Well that Ends_ Ivan Morison

All’s Well that Ends_ Ivan Morison