2010, Vancouver, Canada

Plaza

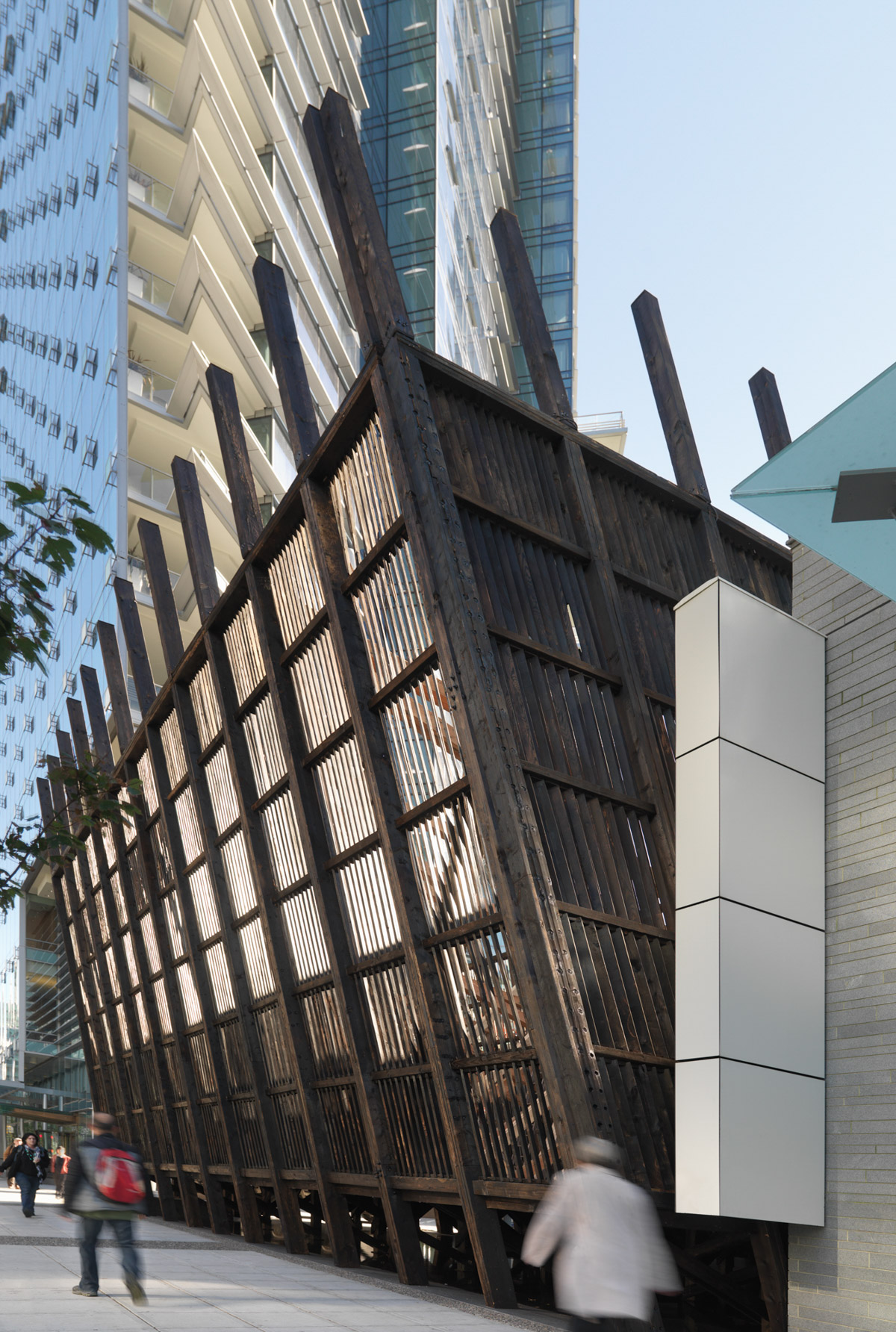

Timber, 12 x 11 x 20 m

Installed at Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite, West Georgia Street, Vancouver

Commissioned by Vancouver Art Gallery and funded by the

City of Vancouver through the Public Art Program, 2010–11

‘A frozen moment of decline. A forceful reordering, held and kept in a perfect new geometry. The grid of the modern city and the lives within them need a violent realigning to create the conditions for happiness. It is these events that can move the collective consciousness of a city towards a new more dynamic view of itself, and a city more suited to our psyches. Only through individual violent and subversive acts and larger societal shifts alongside cataclysmic events will its residents find true happiness. A blueprint for happiness.’

Ivan Morison

Built entirely from salvaged wood – a material with particular resonance on the Pacific Northwest Coast, with its lush forests and rich history of wooden construction – Plaza hovers between sculpture and architecture to reimagine the modern skyscraper at its very limits. The work was situated at Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite, an outdoor space designated for a rotating series of temporary public artworks. The site is adjacent to what was then the tallest building in the city: Living Shangri-La, a 62-storey skyscraper development. This area of the city is home to many similar structures – a sea of grey concrete, steel grids, and glass reflecting the sky and surrounding mountains.

Against this homogeneous landscape, the Morisons’ utopian proposal stood in stubborn contradistinction. Rising three storeys high, the walls of the pavilion leaned out towards the street as if they had been torqued in all directions by an extraordinary force or seismic shift. As Kathleen Ritter, curator at Vancouver Art Gallery, wrote at the time: ‘Plaza evokes a pivotal moment of architectural and societal transformation and metaphorically suggests that the mechanisms that underpin the urban fabric are far more fragile than we imagine. We can infer from its burned surface and collapsing form a cautionary tale for the future, and an invocation to transform the modern city.

This invocation is equally evident in the process and the incredible energy Heather and Ivan Morison brought to this ambitious large-scale project. The construction of Plaza generated a broad community-based effort in which a wide range of people generously donated materials and labour – lumber, hardware, propane, architectural and engineering expertise – while an army of volunteers offered their time and energy to mill and burn countless feet of timber. The coming together of various people in this enormous undertaking evoked how a community might respond in the face of a catastrophe by building collaboratively with shared skills, available resources and salvaged materials – a process that suggests a strategy for survival in the face of unexpected change.’

An opening on one side of Plaza invited visitors to enter the space via a long ramp. Inside, the structure opened up into a spacious pavilion, its roof open to the sky. Depending on one’s position in the space, different slices of the city became visible through the angled louvres in the walls. The space was open all day and night – an invitation for people to access the site and, as they entered, become part of the artwork.

Ivan Morison

Built entirely from salvaged wood – a material with particular resonance on the Pacific Northwest Coast, with its lush forests and rich history of wooden construction – Plaza hovers between sculpture and architecture to reimagine the modern skyscraper at its very limits. The work was situated at Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite, an outdoor space designated for a rotating series of temporary public artworks. The site is adjacent to what was then the tallest building in the city: Living Shangri-La, a 62-storey skyscraper development. This area of the city is home to many similar structures – a sea of grey concrete, steel grids, and glass reflecting the sky and surrounding mountains.

Against this homogeneous landscape, the Morisons’ utopian proposal stood in stubborn contradistinction. Rising three storeys high, the walls of the pavilion leaned out towards the street as if they had been torqued in all directions by an extraordinary force or seismic shift. As Kathleen Ritter, curator at Vancouver Art Gallery, wrote at the time: ‘Plaza evokes a pivotal moment of architectural and societal transformation and metaphorically suggests that the mechanisms that underpin the urban fabric are far more fragile than we imagine. We can infer from its burned surface and collapsing form a cautionary tale for the future, and an invocation to transform the modern city.

This invocation is equally evident in the process and the incredible energy Heather and Ivan Morison brought to this ambitious large-scale project. The construction of Plaza generated a broad community-based effort in which a wide range of people generously donated materials and labour – lumber, hardware, propane, architectural and engineering expertise – while an army of volunteers offered their time and energy to mill and burn countless feet of timber. The coming together of various people in this enormous undertaking evoked how a community might respond in the face of a catastrophe by building collaboratively with shared skills, available resources and salvaged materials – a process that suggests a strategy for survival in the face of unexpected change.’

An opening on one side of Plaza invited visitors to enter the space via a long ramp. Inside, the structure opened up into a spacious pavilion, its roof open to the sky. Depending on one’s position in the space, different slices of the city became visible through the angled louvres in the walls. The space was open all day and night – an invitation for people to access the site and, as they entered, become part of the artwork.

'Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr. Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months.'

The opening line of J.G. Ballard’s 1975 dystopian novel, High-Rise, foreshadows the eventual downfall of its characters and their surroundings as its principal character, Laing, calmly tucks into a canine dinner. Yet the real protagonist of the novel is the high-rise itself—a 40-storey, 1,000-unit, modernist apartment block—a building that, by the very nature of its design, inspires its residents to abandon all form of humane conduct and descend into social chaos.

If Ballard’s cautious tale had any bearing on the minds of architects and urban planners today, we would not find ourselves surrounded by acres of high-rises, an architectural typology well known to the city of Vancouver. Typical of the genre, Ballard’s text suggests that architecture scripts social stratification, where hierarchical relationships between residents are determined, quite literally, by the level of one’s apartment. By this logic, if we were to conceptualize architecture in a fundamentally different way, would this also produce alternatives for social relationships?

Heather and Ivan Morison’s site-specific public artwork, Plaza, re-imagines this architectural form—the modern skyscraper—at its very limits. Plaza is an open wooden structure that, by the nature of the material alone, stands in stark contrast to its concrete and glass surroundings. Its base is balanced on stilts and raised above a pool of water. Its walls rise nearly three storeys and lean out toward the street as if a massive seismic shift has torqued their right angles askew. The walls are made of heavy timber beams, burned to a dark charcoal using a traditional Japanese technique called shou-sugi-ban for preserving and protecting wood from the elements. The walls are braced by enormous diagonal supports, forming a complex interior scaffolding with wood that is left raw as if to suggest this is a more recent addition to the structure, temporarily holding it in place. Plaza is built entirely with wood—a material with particular resonance on the Pacific Northwest Coast with its lush rainforests and rich history of wooden construction. Wood for Plaza was salvaged from beaches, development sites and construction yards throughout Vancouver, forming a veritable index of available material in the city at the moment of construction.

An opening on one side of Plaza invites visitors to enter the space via a long ramp. Inside, the structure opens up into a spacious pavilion, its roof open to the sky. Depending on one’s position in the space, different slices of the city become visible through the angled louvres in the walls. The skewed grid of Plaza’s walls clashes with the grid of the city’s surrounding buildings, at times appearing as if the city itself has started to tilt. The space is open all day and night—an invitation for people to access the site and, as they enter, become part of the artwork.

Plaza is situated at Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite, an outdoor space designated for a rotating series of temporary public artworks. The site is located adjacent to the tallest building in the city at this time: Living Shangri-La, a 62-storey skyscraper development. This area of the city is home to many similar structures—a sea of grey concrete, steel grids and glass reflecting the sky and surrounding mountains. Against this homogeneous landscape, the Morisons’ utopian proposal stands in stubborn contradistinction.

Following this logic, Plaza mimics the most prosaic form of the urban built environment—the gridded box—but forcefully twists it by a mere eight-degree shift, enough for its walls to seem on the verge of collapse. This warping is halted at a precise point, suspending the structure in a play of distortions and perceived imbalances, where it appears to be carefully held in balance between falling and flight, weight and levity, solidity and transparency; a precarious tension often held in artworks by the Morisons. Plaza evokes a pivotal moment of architectural and societal transformation and metaphorically suggests that the mechanisms that underpin the urban fabric are far more fragile than we imagine. We can infer from its burned surface and collapsing form a cautionary tale for the future, and an invocation to transform the modern city.

This invocation is equally evident in the process and the incredible energy Heather and Ivan Morison brought to this ambitious large-scale project. The construction of Plaza generated a broad community-based effort in which a wide range of people generously donated materials and labour—lumber, hardware, propane, architectural and engineering expertise—while an army of volunteers offered their time and energy to mill and burn countless feet of timber. The coming together of various people in this enormous undertaking evoked how a community might respond in the face of a catastrophe by building collaboratively with shared skills, available resources and salvaged materials—a process that suggests a strategy for survival in the face of unexpected change.

As a result of this massive effort and its resulting imposing presence in the streets, Plaza has become a destination for many, a site to frequent and to explore. People gather to eat lunch, take haven from the din of the city or marvel at the sheer scale of an artwork that resists its surrounds with a sculptural grace. As the sun sets and the lights on the upper posts cast an ethereal glow on the space, illuminating the structure from within, Plaza becomes a beacon of possibility for the future.

Kathleen Ritter, Vancouver Art Gallery, 2011

The opening line of J.G. Ballard’s 1975 dystopian novel, High-Rise, foreshadows the eventual downfall of its characters and their surroundings as its principal character, Laing, calmly tucks into a canine dinner. Yet the real protagonist of the novel is the high-rise itself—a 40-storey, 1,000-unit, modernist apartment block—a building that, by the very nature of its design, inspires its residents to abandon all form of humane conduct and descend into social chaos.

If Ballard’s cautious tale had any bearing on the minds of architects and urban planners today, we would not find ourselves surrounded by acres of high-rises, an architectural typology well known to the city of Vancouver. Typical of the genre, Ballard’s text suggests that architecture scripts social stratification, where hierarchical relationships between residents are determined, quite literally, by the level of one’s apartment. By this logic, if we were to conceptualize architecture in a fundamentally different way, would this also produce alternatives for social relationships?

Heather and Ivan Morison’s site-specific public artwork, Plaza, re-imagines this architectural form—the modern skyscraper—at its very limits. Plaza is an open wooden structure that, by the nature of the material alone, stands in stark contrast to its concrete and glass surroundings. Its base is balanced on stilts and raised above a pool of water. Its walls rise nearly three storeys and lean out toward the street as if a massive seismic shift has torqued their right angles askew. The walls are made of heavy timber beams, burned to a dark charcoal using a traditional Japanese technique called shou-sugi-ban for preserving and protecting wood from the elements. The walls are braced by enormous diagonal supports, forming a complex interior scaffolding with wood that is left raw as if to suggest this is a more recent addition to the structure, temporarily holding it in place. Plaza is built entirely with wood—a material with particular resonance on the Pacific Northwest Coast with its lush rainforests and rich history of wooden construction. Wood for Plaza was salvaged from beaches, development sites and construction yards throughout Vancouver, forming a veritable index of available material in the city at the moment of construction.

An opening on one side of Plaza invites visitors to enter the space via a long ramp. Inside, the structure opens up into a spacious pavilion, its roof open to the sky. Depending on one’s position in the space, different slices of the city become visible through the angled louvres in the walls. The skewed grid of Plaza’s walls clashes with the grid of the city’s surrounding buildings, at times appearing as if the city itself has started to tilt. The space is open all day and night—an invitation for people to access the site and, as they enter, become part of the artwork.

Plaza is situated at Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite, an outdoor space designated for a rotating series of temporary public artworks. The site is located adjacent to the tallest building in the city at this time: Living Shangri-La, a 62-storey skyscraper development. This area of the city is home to many similar structures—a sea of grey concrete, steel grids and glass reflecting the sky and surrounding mountains. Against this homogeneous landscape, the Morisons’ utopian proposal stands in stubborn contradistinction.

Following this logic, Plaza mimics the most prosaic form of the urban built environment—the gridded box—but forcefully twists it by a mere eight-degree shift, enough for its walls to seem on the verge of collapse. This warping is halted at a precise point, suspending the structure in a play of distortions and perceived imbalances, where it appears to be carefully held in balance between falling and flight, weight and levity, solidity and transparency; a precarious tension often held in artworks by the Morisons. Plaza evokes a pivotal moment of architectural and societal transformation and metaphorically suggests that the mechanisms that underpin the urban fabric are far more fragile than we imagine. We can infer from its burned surface and collapsing form a cautionary tale for the future, and an invocation to transform the modern city.

This invocation is equally evident in the process and the incredible energy Heather and Ivan Morison brought to this ambitious large-scale project. The construction of Plaza generated a broad community-based effort in which a wide range of people generously donated materials and labour—lumber, hardware, propane, architectural and engineering expertise—while an army of volunteers offered their time and energy to mill and burn countless feet of timber. The coming together of various people in this enormous undertaking evoked how a community might respond in the face of a catastrophe by building collaboratively with shared skills, available resources and salvaged materials—a process that suggests a strategy for survival in the face of unexpected change.

As a result of this massive effort and its resulting imposing presence in the streets, Plaza has become a destination for many, a site to frequent and to explore. People gather to eat lunch, take haven from the din of the city or marvel at the sheer scale of an artwork that resists its surrounds with a sculptural grace. As the sun sets and the lights on the upper posts cast an ethereal glow on the space, illuminating the structure from within, Plaza becomes a beacon of possibility for the future.

Kathleen Ritter, Vancouver Art Gallery, 2011

Photographers’ credits

Installation images_ Rachel Topham / Other images_Ivan Morison

Installation images_ Rachel Topham / Other images_Ivan Morison