2009, Bristol, UK / Wakefield, UK

Black Cloud

Scorched timber, 8 x 12 x 21 m

Originally commissioned by Situations for Victoria Park, Bristol

Relocated in 2011 to The Hepworth, Wakefield, supported by Art in Yorkshire and then relocated again in 2013 to Eastside Projects, Birmingham, UK

First installed in Victoria Park, Bristol, in the summer and autumn of 2009, Black Cloud was a towering wooden pavilion inspired by the large communal dwellings of the Yanomami tribe of the Amazon, which can house up to four hundred people. It was erected over the course of just one day through a process known as barn-raising. Common in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century rural North America, barn-raising was a collective action of a community in which a barn was built or rebuilt for one of its members. Inherent in the practice was the principle of reciprocity: while participation was mandatory for all able-bodied community members, who had to assist in the build without being paid, each participant could expect the same support if the need arose. The tradition continues to this day in some parts of the United States and Canada.

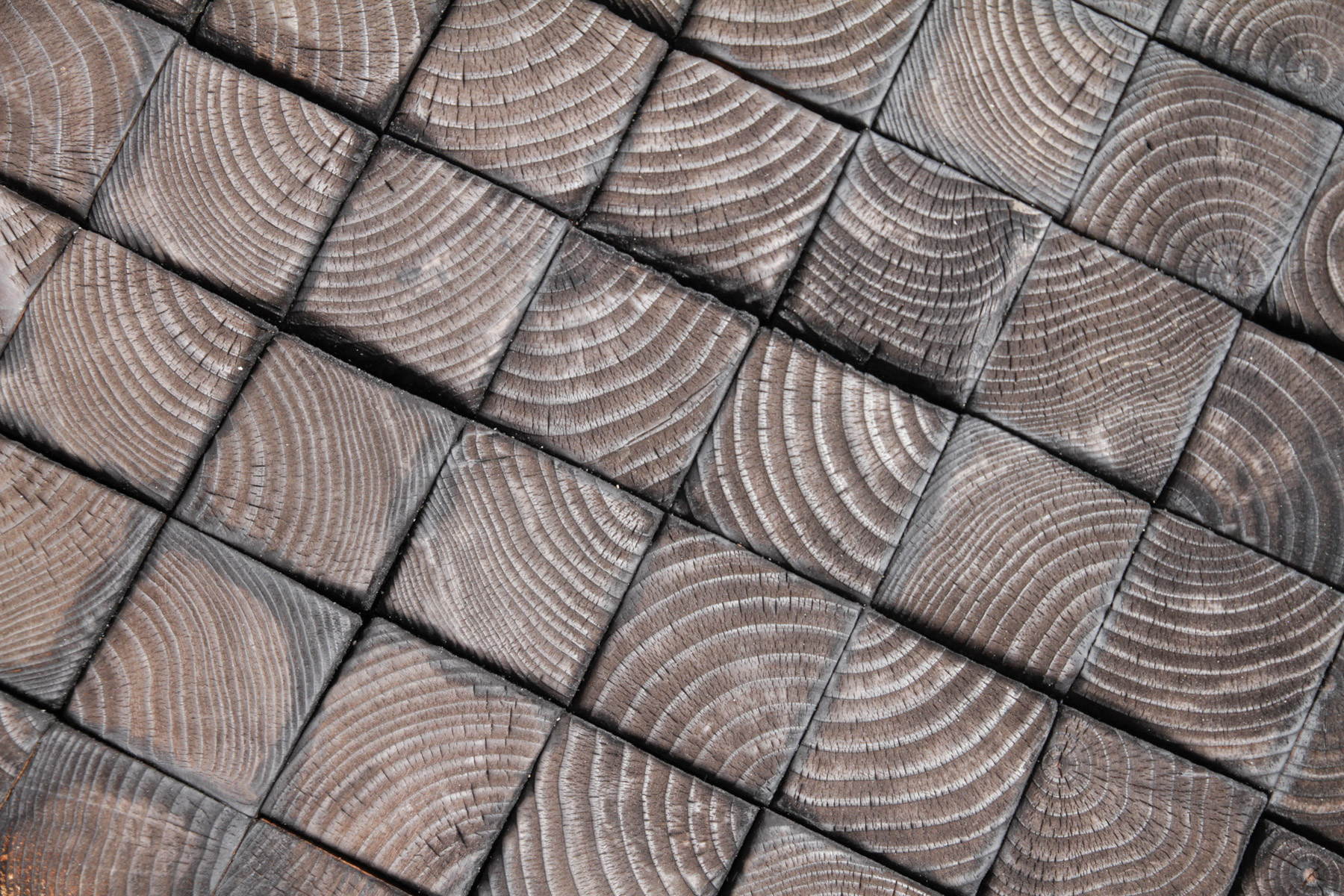

The artists conceived the work during a month-long Arts and Ecology residency in Bristol in 2007, organized by the RSA Arts and Ecology programme and Situations. They enlisted volunteers to come together to construct the open-topped structure in just twelve hours. It was formed from wood taken from trees in the Morisons’ arboretum, which was then protected from the elements by a traditional Japanese scorching technique.

The artists conceived the work during a month-long Arts and Ecology residency in Bristol in 2007, organized by the RSA Arts and Ecology programme and Situations. They enlisted volunteers to come together to construct the open-topped structure in just twelve hours. It was formed from wood taken from trees in the Morisons’ arboretum, which was then protected from the elements by a traditional Japanese scorching technique.

The process not only made the pavilion weatherproof, it also left the surface a charcoal colour. According to the artists’ own dark, dystopian narrative, the structure was proposed as a shelter for a future apocalyptic world scorched black by the unrelenting sun.

Like a contemporary folly – an idiosyncratic architectural statement usually found in eighteenth-century private estates rather than public parks – this mysterious, blackened, jagged insect-like structure looked incongruous as it crept across the well-tended landscape. Always designed to be temporary, it remained in place for only four months, acting as a performance venue that gathered around it a growing community, and was open for park users, local residents, groups, and organizations to carry out their own events for free.

Black Cloud was repositioned and modified in response to the backdrop of The Hepworth gallery in Wakefield and became a performance pavilion for the people of the town. In its final iteration, it morphed with an existing work, Pleasure Island, and became Black Pleasure at Eastside Projects in Birmingham (see pp. 330–1), until it was dismantled permanently in 2018. It now fuels the wood burner in the artists’ studio.

Like a contemporary folly – an idiosyncratic architectural statement usually found in eighteenth-century private estates rather than public parks – this mysterious, blackened, jagged insect-like structure looked incongruous as it crept across the well-tended landscape. Always designed to be temporary, it remained in place for only four months, acting as a performance venue that gathered around it a growing community, and was open for park users, local residents, groups, and organizations to carry out their own events for free.

Black Cloud was repositioned and modified in response to the backdrop of The Hepworth gallery in Wakefield and became a performance pavilion for the people of the town. In its final iteration, it morphed with an existing work, Pleasure Island, and became Black Pleasure at Eastside Projects in Birmingham (see pp. 330–1), until it was dismantled permanently in 2018. It now fuels the wood burner in the artists’ studio.

The Black Cloud, a new public artwork by Heather and Ivan Morison, is a towering wooden pavilion inspired by the Amazonian dwellings of the Yanomamo tribe. Constructed using the Amish principles of communal participation, it is protected from the elements by an ancient Japanese scorching technique. The paneled structure is further overlaid with the artists’ own dark narrative: the Morisons’ propose that it as a shelter for a future apocalyptic world scorched black by the unrelenting sun. Hybrid in style, The Black Cloud in turn reflects many of the references that oscillate throughout the artists’ wider practice, including the prophetic visions of twentieth century science fiction writers and the urgent contemporary concerns of the Arts & Ecology movement, as well as the real world application of collectivist ideals within controlled environments.

The Black Cloud’s hybrid nature also extends to its function; it is both a sculpture and a designated platform for public events, the first of which, The Shape of Things to Come, is a day-long festival which simultaneously celebrates and facilitates the arrival of The Black Cloud in Victoria Park, Bristol. Rather than the official unveiling ceremony that accompanies the majority of public art projects, the challenges of erecting this monumental pavilion are instead played out in full view, as a team of volunteers from the local area erect The Black Cloud over the course of the day, pooling their energy and resources as if they were villagers raising an Amish barn. They are joined in turn by a large crowd who come to watch, offer support and enjoy the additional efforts of other volunteers who supply refreshments and entertainment including live music, story-telling and den building for young enthusiasts who want to create their own version. The Shape of Things to Come thus incorporates everyone present into a total art work in which labour and leisure becomes a form of performance, as well as a means to an end. The structure itself, the focal point of all this activity, is ultimately finished just over twelve hours later, with the core team labouring on through sun, rain and darkness; its eventual completion a testament to the collective effort of all those involved.

The Black Cloud is activated across summer and into autumn by other participatory events instigated by the Morisons. These include a local music festival entitled Cloud Jam; a discussion forum on alternative futures with contributions from scientists, theorists and fiction writers called How To Prosper During The Coming Bad Years and the final event, a dark narrative, Black Dog Times, in which puppets (another recurring motif in the artists’ practice), mark its departure from Victoria Park. It is here, by relaying not only The Black Cloud’s arrival, but also its departure, that I reveal my earlier temporal slippage – the use of a permanent present tense, the ‘now time’ employed for vivid effect when describing artworks – which deceptively masks the fact that The Black Cloud is no more. Despite its monumental nature, the sculpture was always explicitly time based, intended to reside for just four months in a corner of the park, before being painstaking removed piece by piece, so that only faint marks on the grass indicate that anything was ever there.

In terms of art world conventions, four months may either be considered a particularly short period for a significant piece of public sculpture or an unusually long time for an event. With its median duration, The Black Cloud is therefore perhaps closer to Bienniale or World’s Fair time where spectacular public pavilions are erected for temporary use over several months, animated at first and then gradually abandoned, ultimately dismantled or left to decay. Whilst operating within a similar ‘Expo time’, it should be noted that temporality was part of the impetus to continuously activate it, with daily usage gaining rather than losing momentum as its allotted slot in the park came to an end. The structure was therefore not left to dwindle into obscurity but was regularly activated by the various communities of interest who live near by and who, in between officially programmed events, booked it as a place to hold parties and meetings, used it as a shelter in which to casually hang out, as well as making use of its aesthetic function as a sculpture that could be walked up to, in and around or simply contemplated from a distance.

Thus, unlike the purpose-built festival pavilion which is often left stranded in a semi-regenerated post-industrial area after international audiences move on, The Black Cloud was a specifically localised, one-off project that had taken many years to develop and negotiate with a specific constituent group: the regular users of a well tended park who wanted a structure with multiple potential uses. And yet, whilst these desires were largely fulfilled, I shall here resist the well-worn rhetoric of ‘generosity’ that so often accompanies artworks which involve degrees of social engagement. Such idealistic notions of selflessness in turn only serve to perpetuate the relentlessly positivist discourse of normative public art; namely the idea that public art operates as a benign gift, as something that should be conceived as averagely likeable; designed for all yet ultimately owned by no one.

The Black Cloud’s hybrid nature also extends to its function; it is both a sculpture and a designated platform for public events, the first of which, The Shape of Things to Come, is a day-long festival which simultaneously celebrates and facilitates the arrival of The Black Cloud in Victoria Park, Bristol. Rather than the official unveiling ceremony that accompanies the majority of public art projects, the challenges of erecting this monumental pavilion are instead played out in full view, as a team of volunteers from the local area erect The Black Cloud over the course of the day, pooling their energy and resources as if they were villagers raising an Amish barn. They are joined in turn by a large crowd who come to watch, offer support and enjoy the additional efforts of other volunteers who supply refreshments and entertainment including live music, story-telling and den building for young enthusiasts who want to create their own version. The Shape of Things to Come thus incorporates everyone present into a total art work in which labour and leisure becomes a form of performance, as well as a means to an end. The structure itself, the focal point of all this activity, is ultimately finished just over twelve hours later, with the core team labouring on through sun, rain and darkness; its eventual completion a testament to the collective effort of all those involved.

The Black Cloud is activated across summer and into autumn by other participatory events instigated by the Morisons. These include a local music festival entitled Cloud Jam; a discussion forum on alternative futures with contributions from scientists, theorists and fiction writers called How To Prosper During The Coming Bad Years and the final event, a dark narrative, Black Dog Times, in which puppets (another recurring motif in the artists’ practice), mark its departure from Victoria Park. It is here, by relaying not only The Black Cloud’s arrival, but also its departure, that I reveal my earlier temporal slippage – the use of a permanent present tense, the ‘now time’ employed for vivid effect when describing artworks – which deceptively masks the fact that The Black Cloud is no more. Despite its monumental nature, the sculpture was always explicitly time based, intended to reside for just four months in a corner of the park, before being painstaking removed piece by piece, so that only faint marks on the grass indicate that anything was ever there.

In terms of art world conventions, four months may either be considered a particularly short period for a significant piece of public sculpture or an unusually long time for an event. With its median duration, The Black Cloud is therefore perhaps closer to Bienniale or World’s Fair time where spectacular public pavilions are erected for temporary use over several months, animated at first and then gradually abandoned, ultimately dismantled or left to decay. Whilst operating within a similar ‘Expo time’, it should be noted that temporality was part of the impetus to continuously activate it, with daily usage gaining rather than losing momentum as its allotted slot in the park came to an end. The structure was therefore not left to dwindle into obscurity but was regularly activated by the various communities of interest who live near by and who, in between officially programmed events, booked it as a place to hold parties and meetings, used it as a shelter in which to casually hang out, as well as making use of its aesthetic function as a sculpture that could be walked up to, in and around or simply contemplated from a distance.

Thus, unlike the purpose-built festival pavilion which is often left stranded in a semi-regenerated post-industrial area after international audiences move on, The Black Cloud was a specifically localised, one-off project that had taken many years to develop and negotiate with a specific constituent group: the regular users of a well tended park who wanted a structure with multiple potential uses. And yet, whilst these desires were largely fulfilled, I shall here resist the well-worn rhetoric of ‘generosity’ that so often accompanies artworks which involve degrees of social engagement. Such idealistic notions of selflessness in turn only serve to perpetuate the relentlessly positivist discourse of normative public art; namely the idea that public art operates as a benign gift, as something that should be conceived as averagely likeable; designed for all yet ultimately owned by no one.

The Black Cloud was too ambiguous, too ominous in tone to be unproblematically affirmative. Crouched insect-like on paneled legs, it was defiantly incongruous; a blackened cyber-punk tinged structure, resolutely out of place against quaint Victorian terraces. Whilst brought into being through considerable community consultation, The Black Cloud is still first and foremost the product of the artists’ singular vision and therefore belongs to a wider artistic practice which contains its own conceptual logic, as well to the participants who use it. The Black Cloud is therefore also a formalist provocation, and an art work with open-ended intent, rather than something that is essentially generous.

Another reading of this unique architectural statement, beyond the discourse of public sculpture, is to view it as a contemporary folly, that most idiosyncratic of architectural statements which usually inhabit eighteenth century private estates rather than public parks. This analogy has further parallels with The Black Cloud’s dystopian narrative too. As Christopher Woodward observes in “In Ruins”, a study of the lasting appeal of the aesthetics of decay, dissolution and disaster in Western culture, the folly, most commonly a partially constructed faux Roman Temple, medieval Abby or Egyptian tomb, acts as a memento mori that offers “a dialogue between an incomplete reality and the imagination of the spectator”. A similar dialogue between imagination and reality must be undertaken by the viewer when contemplating The Black Cloud, yet, instead of being asked to fill in the intentionally missing elements of a fake classical ruin, we are asked to change the setting around the blackened jagged structure, from a well tended, verdant park to a sun blasted desert devastating affected by climate change. The primary temporal displacement offered by the Morisons’ folly is therefore not between the present and a lost civilization, but between the current moment and a potential future catastrophe.

Whilst the work’s post-apocalyptic overtones and faux-sun blackened panels act as their own form of warning against ignoring existing signs of climate change, its status as an ‘environmental’ art work - it was originally commissioned through an Arts & Ecology residency - has been disputed by those who prefer their art to be more explicitly carbon neutral. The Morisons and their commissioners Situations have, however, been entirely open about the considerable environmental impact of making and installing the work; the trees used from the artists’ arboretum will not grow back to full height for several years and the JCBs used on the day, along with the protective scorching techniques, are also far from environmentally sustainable. Both parties propose instead that The Black Cloud does not seek to be literally ‘environmentally friendly’, but acts as a provocation to our complacency, raising awareness through its spectral form, even if there is an environmental cost in doing so. The Arts & Ecology movement, it should also be noted, is as pluralistic, and therefore as seemingly contradictory, as its precursor Land Art, which embraced both the light touch of Fulton and Long, as well as the spectacular mechanized constructions of Smithson. That does not ultimately mean that the artists have the absolute moral high ground in such debates, only that there are different ways of defining and being ecologically ‘conscious’.

In conclusion, The Black Cloud was not just hybrid in style, mixing vernacular architecture with twenty-first century building techniques, but also in function and attitude too; a Sculpture/Pavilion that was dystopian and utopian in equal measure, encapsulating a pessimistic vision of the future in its dark jagged panels, yet at the same time operating as a free space for debates on alternative worlds. It was a work that embraced ambiguity, a structure that could be categorized in many different ways; as a mysterious temporary landmark; a new meeting point in a well used public space; a open top shelter with a unique vista onto the sky; a platform for collective activity; a place to hide from the world; a stage for performance; a portent from soon to be ruined future and, most simply of all, a remarkably sculptural form that, when encountered for the first time on a misty winter morning, provided a foil for the imagination. It was also, to return briefly to the commemorative intentions of traditional public art, still a monument of sorts; a temporary monument to the collective efforts and labour of those who built it and those who activated it. The Black Cloud is therefore public art not just in the sense that its first and last days were lived outside in public view, but because of the different models of communal participation that it elicited. Unlike many obscure, neglected or unloved public art works, it did not outstay its welcome nor did it linger long enough to become commonplace. As a well documented art work it lives on in an official archive and via a hundred dispersed mobile phone camera images, yet it also exists within memory too, as that powerful-presence-in-absence which haunts consciousness, and through urban myth and rumour: a myth which maintains that, for a short time, a mysterious black cloud came to reside in Victoria Park and the rumour which warns of the day it will come back.

Marie-Anne McQuay, critical response to The Black Cloud, 2009

Another reading of this unique architectural statement, beyond the discourse of public sculpture, is to view it as a contemporary folly, that most idiosyncratic of architectural statements which usually inhabit eighteenth century private estates rather than public parks. This analogy has further parallels with The Black Cloud’s dystopian narrative too. As Christopher Woodward observes in “In Ruins”, a study of the lasting appeal of the aesthetics of decay, dissolution and disaster in Western culture, the folly, most commonly a partially constructed faux Roman Temple, medieval Abby or Egyptian tomb, acts as a memento mori that offers “a dialogue between an incomplete reality and the imagination of the spectator”. A similar dialogue between imagination and reality must be undertaken by the viewer when contemplating The Black Cloud, yet, instead of being asked to fill in the intentionally missing elements of a fake classical ruin, we are asked to change the setting around the blackened jagged structure, from a well tended, verdant park to a sun blasted desert devastating affected by climate change. The primary temporal displacement offered by the Morisons’ folly is therefore not between the present and a lost civilization, but between the current moment and a potential future catastrophe.

Whilst the work’s post-apocalyptic overtones and faux-sun blackened panels act as their own form of warning against ignoring existing signs of climate change, its status as an ‘environmental’ art work - it was originally commissioned through an Arts & Ecology residency - has been disputed by those who prefer their art to be more explicitly carbon neutral. The Morisons and their commissioners Situations have, however, been entirely open about the considerable environmental impact of making and installing the work; the trees used from the artists’ arboretum will not grow back to full height for several years and the JCBs used on the day, along with the protective scorching techniques, are also far from environmentally sustainable. Both parties propose instead that The Black Cloud does not seek to be literally ‘environmentally friendly’, but acts as a provocation to our complacency, raising awareness through its spectral form, even if there is an environmental cost in doing so. The Arts & Ecology movement, it should also be noted, is as pluralistic, and therefore as seemingly contradictory, as its precursor Land Art, which embraced both the light touch of Fulton and Long, as well as the spectacular mechanized constructions of Smithson. That does not ultimately mean that the artists have the absolute moral high ground in such debates, only that there are different ways of defining and being ecologically ‘conscious’.

In conclusion, The Black Cloud was not just hybrid in style, mixing vernacular architecture with twenty-first century building techniques, but also in function and attitude too; a Sculpture/Pavilion that was dystopian and utopian in equal measure, encapsulating a pessimistic vision of the future in its dark jagged panels, yet at the same time operating as a free space for debates on alternative worlds. It was a work that embraced ambiguity, a structure that could be categorized in many different ways; as a mysterious temporary landmark; a new meeting point in a well used public space; a open top shelter with a unique vista onto the sky; a platform for collective activity; a place to hide from the world; a stage for performance; a portent from soon to be ruined future and, most simply of all, a remarkably sculptural form that, when encountered for the first time on a misty winter morning, provided a foil for the imagination. It was also, to return briefly to the commemorative intentions of traditional public art, still a monument of sorts; a temporary monument to the collective efforts and labour of those who built it and those who activated it. The Black Cloud is therefore public art not just in the sense that its first and last days were lived outside in public view, but because of the different models of communal participation that it elicited. Unlike many obscure, neglected or unloved public art works, it did not outstay its welcome nor did it linger long enough to become commonplace. As a well documented art work it lives on in an official archive and via a hundred dispersed mobile phone camera images, yet it also exists within memory too, as that powerful-presence-in-absence which haunts consciousness, and through urban myth and rumour: a myth which maintains that, for a short time, a mysterious black cloud came to reside in Victoria Park and the rumour which warns of the day it will come back.

Marie-Anne McQuay, critical response to The Black Cloud, 2009

Photographers’ credits

Black Cloud, Bristol_ Wig Worland / Black Cloud Performance, Wakefield_Jonty Wilde / All other images_Ivan Morison

Black Cloud, Bristol_ Wig Worland / Black Cloud Performance, Wakefield_Jonty Wilde / All other images_Ivan Morison